Since I am Japanese American, I’m often asked about my family and World War II. Specifically, people question if they were sent to one of the eleven internment camps spread over the western United States, all of them in the most inhospitable places imaginable.

I tell them half of my family lived through that shameful history, while the other half did not.

Because my father’s family lived on the West Coast during the years leading up to World War II, they were interned at Poston, Arizona for about three years. My mother’s family on the other hand, resided in rural southeastern Colorado, far enough away from any “threat” they could inflict on a scared but ignorant population.

The internment wasn’t something my dad talked about with us, but I knew how he felt about it. Other than the food we ate at least once a week, a few pieces of artwork around the house and the Protestant church we attended with other Japanese American families, there was little evidence of our heritage. We didn’t learn the Japanese language, go to Japan for travel or retain anything else that distinguished us from others.

Not surprisingly, when the Japanese American National Museum opened thirty years ago in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo district, Dad wasn’t interested to visit. In the four remaining years of his life, he never went. I completely understood and empathized. Why would he want to be reminded of what was one of the most painful periods of his life?

Even with his reluctance, we kids decided to donate to the construction of a glass wall overlooking a narrow garden. His name was imprinted with thousands of others when the museum made them available a few years after its opening – and a year after his passing.

I’ve been to the museum now about a half-dozen times, and each time I try to find Tommy Sakata on that glass pane wall. Since there is no directory for location of the names, we simply to find it on our own.

On my seventh visit to the JANM, I once again didn’t find it, but I paid closer attention to the exhibits, especially in the context of my dad’s experience.

Common Ground

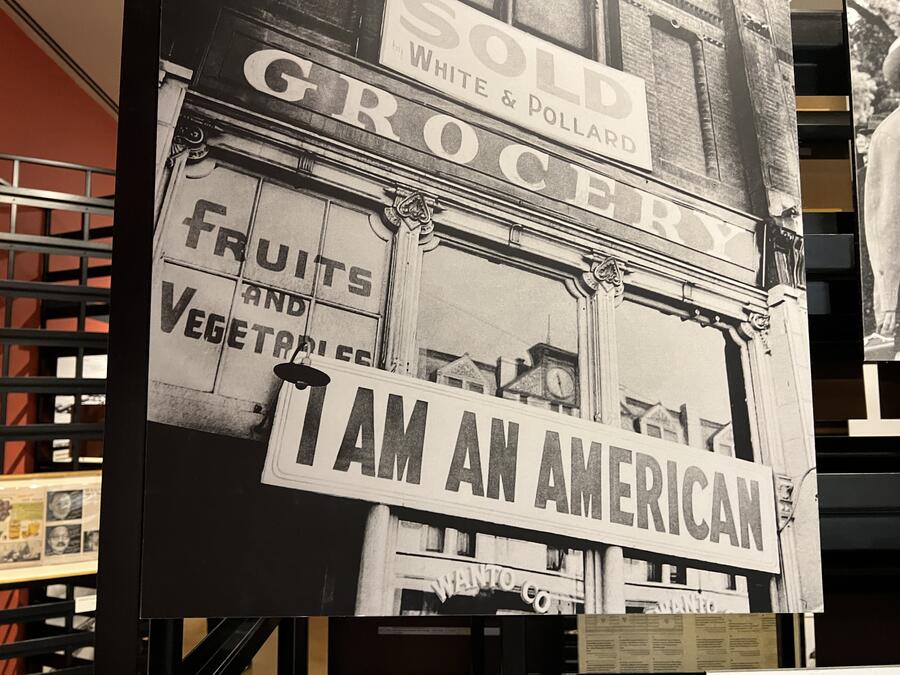

The museum’s only permanent exhibit, "Common Ground", details Japanese immigrants’ arrival in the US in the late 19th century to the redress compensation that was awarded to surviving internees in the 1980s. Understandably, the focus is on the internment and the development of how a grave civil rights injustice of nearly 110,000 Americans could happen.

Just off to the side of the exhibit’s entrance is part of the actual structure from one of the camps, Heart Mountain.

My dad’s father arrived in this country, as many Issei (first generation Japanese), with little money and a suitcase or trunk that looked like these:

I never asked my dad if he went to Japanese language school, like this display shows, but he likely did. He did speak functional Japanese, just enough to communicate with his mother, who knew very little English.

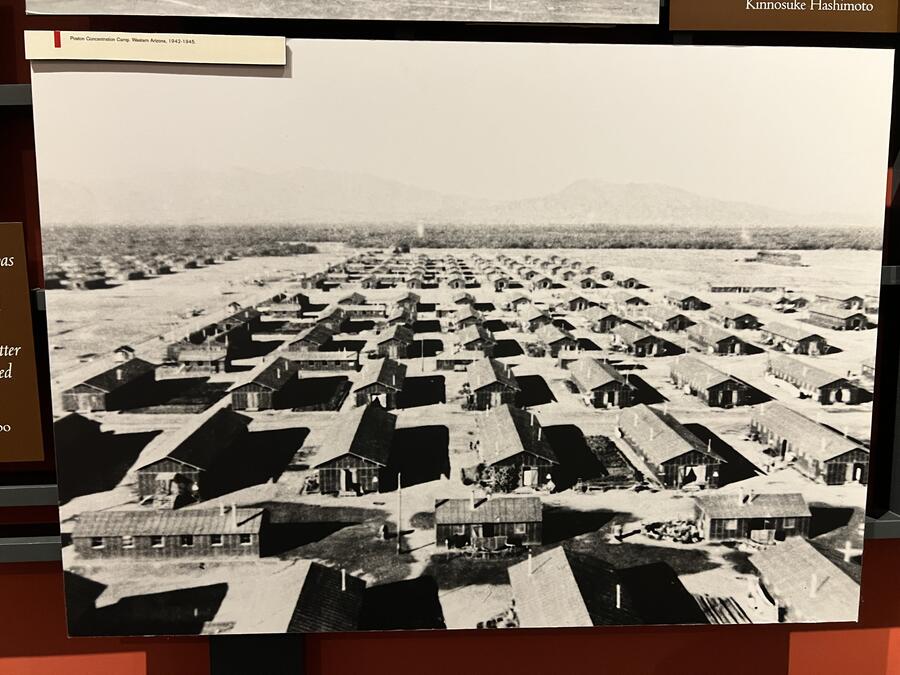

This is a picture of Poston, where my dad’s family lived for almost three years. The second photo is a model of Manzanar, which shows just how large these camps were.

Current exhibitions

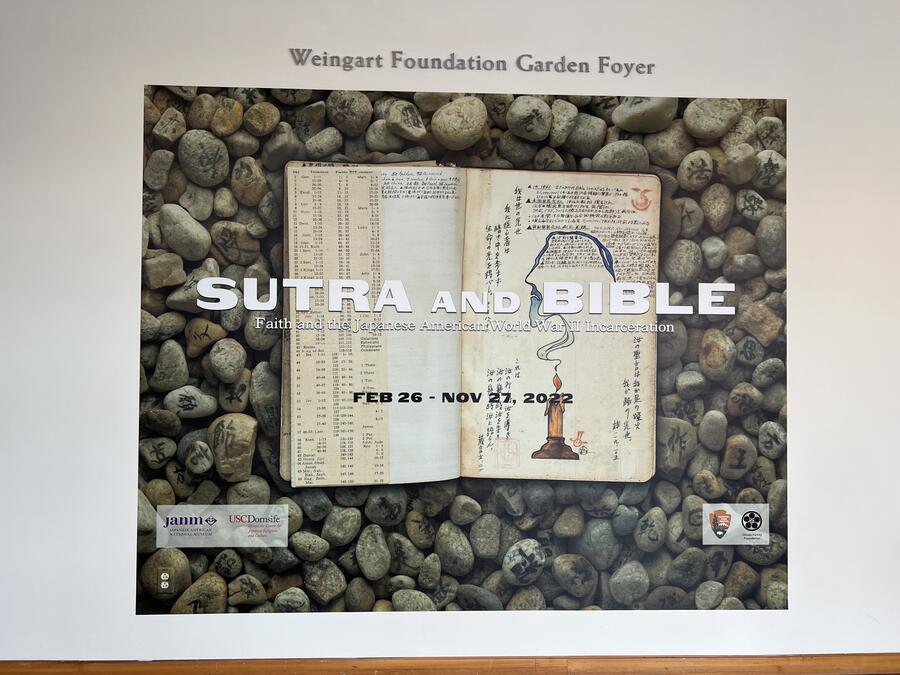

These are temporary exhibits lasting a few months. Two were on display at the time of our visit, but one of them wasn’t completely set up. The second, “Sutra and Bible,” showed how religion affected the lives of Japanese Americans during the internment and life afterwards.

Although my grandfather was Buddhist, he converted to Christianity soon after immigrating here and attended a Presbyterian church. My father was devout, attending church just about every Sunday and encouraging us to pray and study the Bible. He truly lived his faith by example, and I think about how I want to be like him every day.

Virtual and traveling exhibitions

Because of COVID, the JANM developed many exhibitions that could be watched online or in other cities. Virtual visits allow for groups to see the museum from anywhere in the world, while the traveling exhibits are on display at other institutions. The ones that were currently shown were “Tatau” at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu and “Contested Histories” at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City, New York.

I am still not certain if my dad would have visited the JANM if he were still alive. But maybe with the encouragement of my own kids’ interest in their Japanese heritage, he might have.